You almost died after a great white shark attack in your twenties – but since then you've pioneered shark conservation and cage diving. Why?

In hospital after my shark attack, I saw and felt a deep-seated hatred and fear of sharks. There was a saying in those days that the best shark is a dead shark and very little was known about them. From the published stories of my fight for survival I became an instant celebrity, with huge scars right around my chest and on my arm, wrist and hand.

I wanted to find out all I could about these 'ferocious' sharks. I thought we were saddling the sharks with a much more fearful tag than was due. I wanted people to better understand sharks, and to teach by example that sharks are not as bad as they were portrayed.

You developed the first cage for shark diving – how did you come up with the idea?

After my shark attack I was scared to go back in the water as I realised I might not survive another attack like that. It was at the Adelaide Zoo, 7 months after my attack, that I saw lions behind bars in cages.

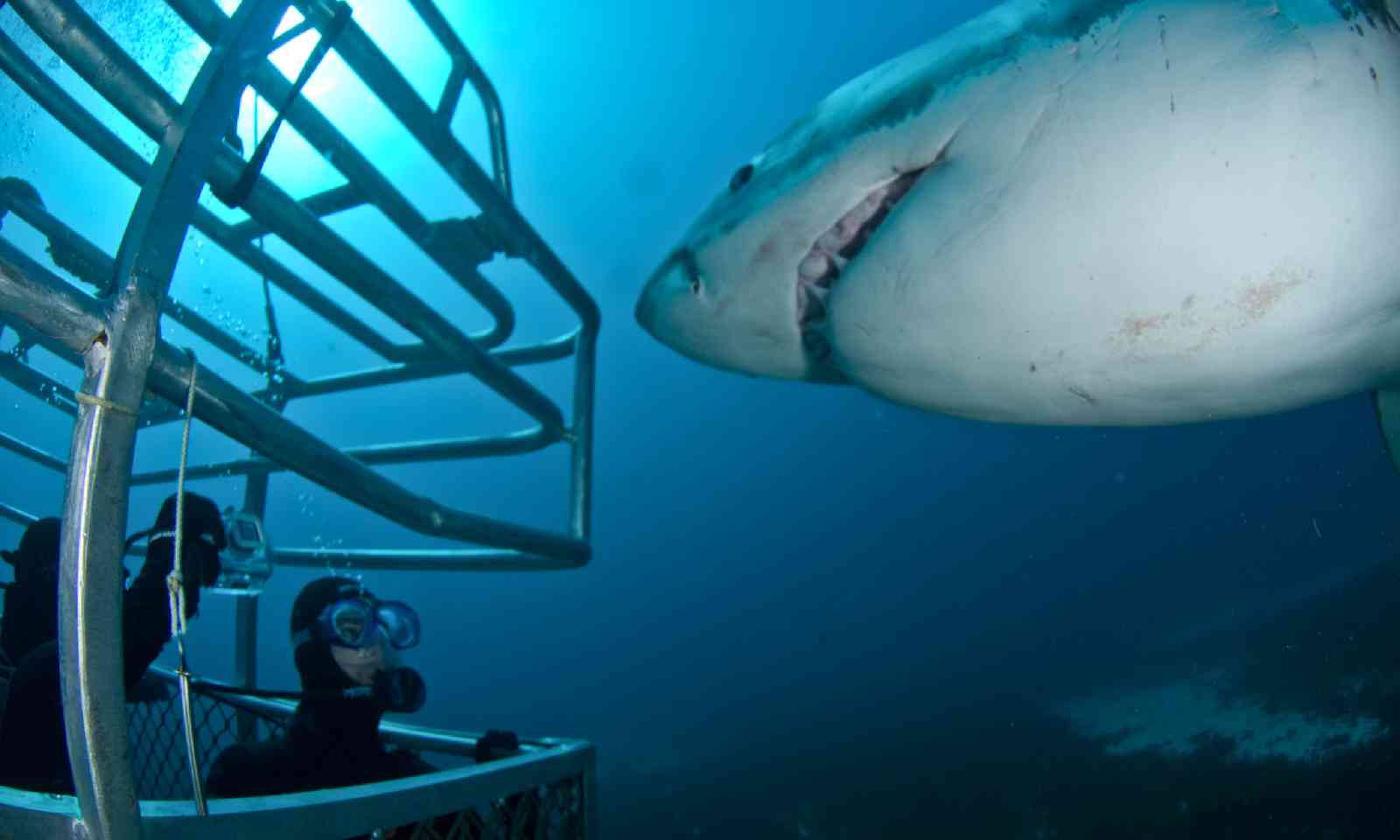

I thought to myself, they are predators, so-called 'man eaters' just like the sharks... maybe I can reverse the role? I’ll make a cage, lower it over the side of a boat where there are great white sharks, get in the cage and see for myself if they are as bad as people say.

I found the sharks were not the crazy man-eaters they were said to be. They didn't race in to get at me, but were keen on our fish bait instead. Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions was born.

Lots of people get sucked in by the media representation of sharks as 'savage' – what insight can you give us into their real behaviour and actions?

There are over 500 species of sharks, with only a handful regarded as potentially dangerous. We have made over 80 documentaries and feature films for 16 countries and led hundreds of tourist and science expeditions, trying to get people to understand the sharks and their important role in our oceans.

Whilst working on documentaries for National Geographic and the Cousteau society I said to the directors that we are not doing the sharks much of a favour by continually showing biting jaws. The answer on both occasions was “We have to get high ratings and give the people what they want”. So we have to try and weave our conservation message into the film to get people to understand.

You also worked with Spielberg on the Jaws movie...

When I took the job as expedition leader to obtain live footage of great white sharks for a big Hollywood shark movie I was very proud and excited. I had no idea it was going to be a movie that would set shark conservation back and frighten so many people out of the water. That was the last thing I wanted.

The film exploited the primal fear we have of being eaten alive and so many people gave up swimming and diving. My job as expedition leader for the film unit in Australia involved a very small man, Carl Rizzo, as a stunt diver – he was so small that he made our 14ft sharks look twice as large.

Neptune Islands

Your conservation work is largely focused on the Neptune Island in South Australia – why is it such a hotspot for sharks?

With their breeding colony of long nose fur seals, the Neptunes are said to be the best restaurant for great whites in South Australia.

From our years of cage diving expeditions my son Andrew has amassed a huge photographic database of great white sharks that have visited the Neptune Islands. We have identified over 400 great whites that visit the islands regularly by checking their sex, size and markings and the colour variations and patterns on their bodies.

Have there been any particularly memorable sharks?

Some of our favourite great whites include Moo, a 4.3m male with big black spots on his body; Elvis, a 4.2m male who is a spectacular breaching shark; and Santa, a large old 4.3m male with an unusual growth on his chin resembling Santa’s beard.

Over 5 years ago a 3m juvenile shark appeared at the Neptune Islands with a packaging strap caught around his gills, threatening to cut him in half. After many attempts to restrain him and cut the strap free, we were finally successful. We named him Chompy, and have been delighted to see him reappear to us again many times over the years.

What kind of shark data do you collect?

In conjunction with scientific institutions like the CSIRO, Flinders University of South Australia and SARDI, our collection of data includes DNA sampling, sonic and satellite tags to determine their migration and site fidelity patterns and length of stay at the Neptune Islands.

How can people help with shark conservation?

People can help by educating themselves and others about the role sharks play in the ocean and why they are important. Sharks are a necessary part of our oceans' ecology – we need them to keep our oceans healthy.

Everyone can also help by not eating shark fin soup or eating shark meat from dubious sources – this is sometimes called 'flake'. It is reported that tens of millions of shark are killed just for shark fin soup.

How do you hope shark conservation will develop in the future?

I am greatly relieved that there are more emerging shark trusts, foundations and charities. 50 years ago, there were none!

Education is the key to conservation. We need documentaries, books and discussions – not just on the sharks but all the creatures in our oceans. Because they are out of sight under the surface of the sea, they are also easily out of mind.

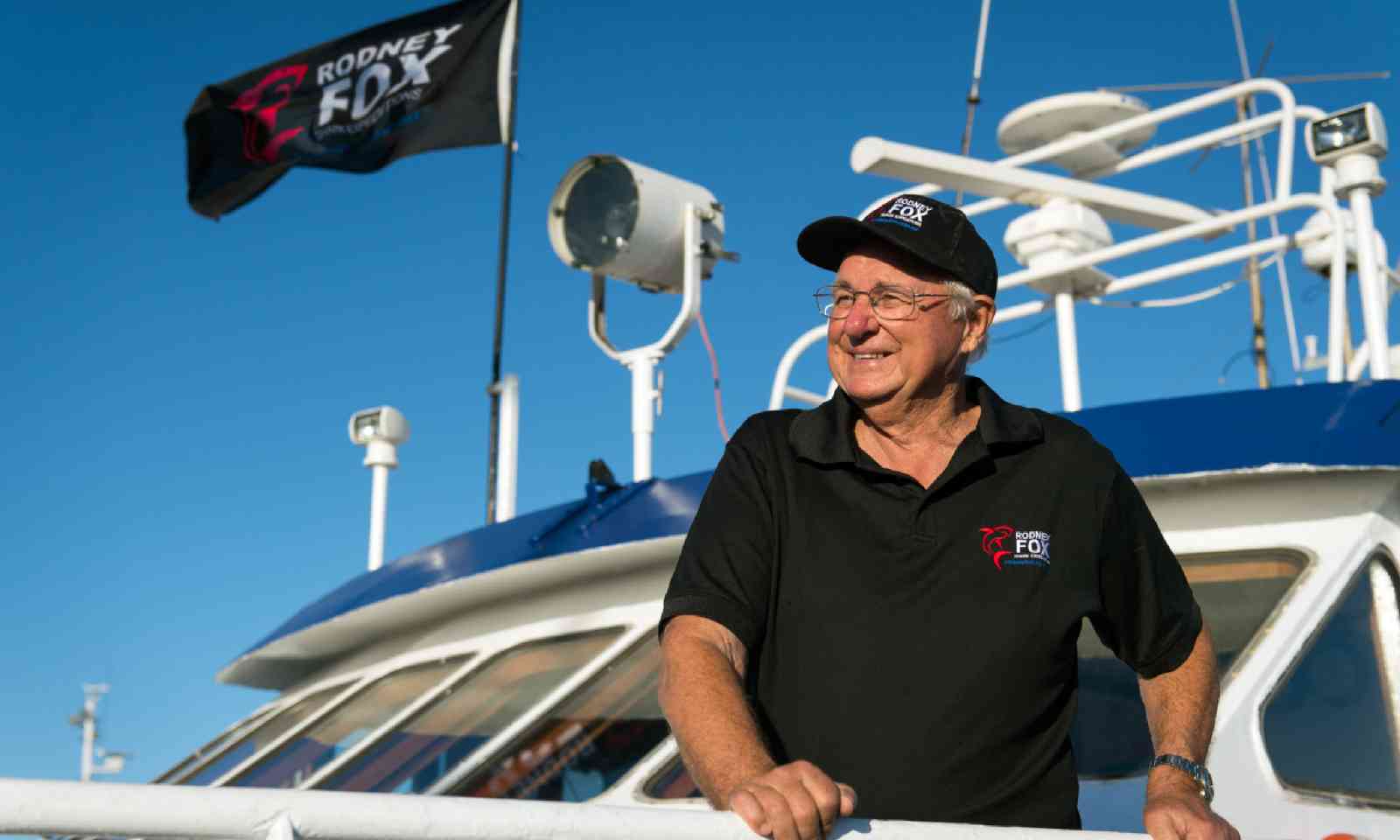

All images: Rodney Fox Expeditions

In hospital after my shark attack, I saw and felt a deep-seated hatred and fear of sharks. There was a saying in those days that the best shark is a dead shark and very little was known about them. From the published stories of my fight for survival I became an instant celebrity, with huge scars right around my chest and on my arm, wrist and hand.

I wanted to find out all I could about these 'ferocious' sharks. I thought we were saddling the sharks with a much more fearful tag than was due. I wanted people to better understand sharks, and to teach by example that sharks are not as bad as they were portrayed.

You developed the first cage for shark diving – how did you come up with the idea?

After my shark attack I was scared to go back in the water as I realised I might not survive another attack like that. It was at the Adelaide Zoo, 7 months after my attack, that I saw lions behind bars in cages.

I thought to myself, they are predators, so-called 'man eaters' just like the sharks... maybe I can reverse the role? I’ll make a cage, lower it over the side of a boat where there are great white sharks, get in the cage and see for myself if they are as bad as people say.

I found the sharks were not the crazy man-eaters they were said to be. They didn't race in to get at me, but were keen on our fish bait instead. Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions was born.

Lots of people get sucked in by the media representation of sharks as 'savage' – what insight can you give us into their real behaviour and actions?

There are over 500 species of sharks, with only a handful regarded as potentially dangerous. We have made over 80 documentaries and feature films for 16 countries and led hundreds of tourist and science expeditions, trying to get people to understand the sharks and their important role in our oceans.

Whilst working on documentaries for National Geographic and the Cousteau society I said to the directors that we are not doing the sharks much of a favour by continually showing biting jaws. The answer on both occasions was “We have to get high ratings and give the people what they want”. So we have to try and weave our conservation message into the film to get people to understand.

You also worked with Spielberg on the Jaws movie...

When I took the job as expedition leader to obtain live footage of great white sharks for a big Hollywood shark movie I was very proud and excited. I had no idea it was going to be a movie that would set shark conservation back and frighten so many people out of the water. That was the last thing I wanted.

The film exploited the primal fear we have of being eaten alive and so many people gave up swimming and diving. My job as expedition leader for the film unit in Australia involved a very small man, Carl Rizzo, as a stunt diver – he was so small that he made our 14ft sharks look twice as large.

Neptune Islands

Your conservation work is largely focused on the Neptune Island in South Australia – why is it such a hotspot for sharks?

With their breeding colony of long nose fur seals, the Neptunes are said to be the best restaurant for great whites in South Australia.

From our years of cage diving expeditions my son Andrew has amassed a huge photographic database of great white sharks that have visited the Neptune Islands. We have identified over 400 great whites that visit the islands regularly by checking their sex, size and markings and the colour variations and patterns on their bodies.

Have there been any particularly memorable sharks?

Some of our favourite great whites include Moo, a 4.3m male with big black spots on his body; Elvis, a 4.2m male who is a spectacular breaching shark; and Santa, a large old 4.3m male with an unusual growth on his chin resembling Santa’s beard.

Over 5 years ago a 3m juvenile shark appeared at the Neptune Islands with a packaging strap caught around his gills, threatening to cut him in half. After many attempts to restrain him and cut the strap free, we were finally successful. We named him Chompy, and have been delighted to see him reappear to us again many times over the years.

What kind of shark data do you collect?

In conjunction with scientific institutions like the CSIRO, Flinders University of South Australia and SARDI, our collection of data includes DNA sampling, sonic and satellite tags to determine their migration and site fidelity patterns and length of stay at the Neptune Islands.

How can people help with shark conservation?

People can help by educating themselves and others about the role sharks play in the ocean and why they are important. Sharks are a necessary part of our oceans' ecology – we need them to keep our oceans healthy.

Everyone can also help by not eating shark fin soup or eating shark meat from dubious sources – this is sometimes called 'flake'. It is reported that tens of millions of shark are killed just for shark fin soup.

How do you hope shark conservation will develop in the future?

I am greatly relieved that there are more emerging shark trusts, foundations and charities. 50 years ago, there were none!

Education is the key to conservation. We need documentaries, books and discussions – not just on the sharks but all the creatures in our oceans. Because they are out of sight under the surface of the sea, they are also easily out of mind.

All images: Rodney Fox Expeditions